Ditch that “mind strengthening” app you just downloaded because an Instagram ad convinced you to (there are for sure gonna be in-app purchases). I have a suggestion for a superior way to beat the aging brain – and it’s free.

Learn a language.

But what does it mean to learn a language to be able to “speak” it?

I’ll tell you what it doesn’t mean. It doesn’t mean becoming a YouTube polyglot.

Recently, there’s been a growing cohort of “influencers” who surprise unsuspecting non-English speakers by seemingly speaking their language fluently.

Don’t feel discouraged if they’ve ever made you feel like a dumb dumb.

Here’s why: most of these so-called polyglots are full of total caca.

Some of them are legit. But many claim to know an outrageous number of languages supposedly learned in record time. In the age of hyper-video editing, I’m not buying their alleged “abilities.”

This dude gets it.

The real marker of speaking a foreign language lies in your competence across the four essential skills – listening, reading, speaking, and writing – aligned with the globally recognized CEFR levels.

This framework provides a clear, measurable standard to assess true language ability.

Here’s how CEFR breaks down proficiency.

The CEFR emphasizes a balance across input and output (listening / reading & speaking / writing). True fluency means you can fluidly apply these skills in real-time, adapting to native speakers without over-relying on translation or rehearsed phrases.

When someone claims to “speak” a language, the question isn’t how many they know but to what CEFR level they can use each of these skills. Anything less? That’s not fluency – it’s just dabbling.

So, the next time someone says, “I speak [such and such],” hit ‘em back with “what level?” They likely won’t even know this framework (or care).

For your purposes, it suffices to say, “I speak level B1 Spanish,” for example.

I’ve traveled to 12+ countries and “speak” 4 languages of varying levels from A2-B2.

Current level: B1

Highest: B2

Goal: To get my level back up in time. I’m also not in the Spanish-speaking world currently, so it’s not high on my priority list.

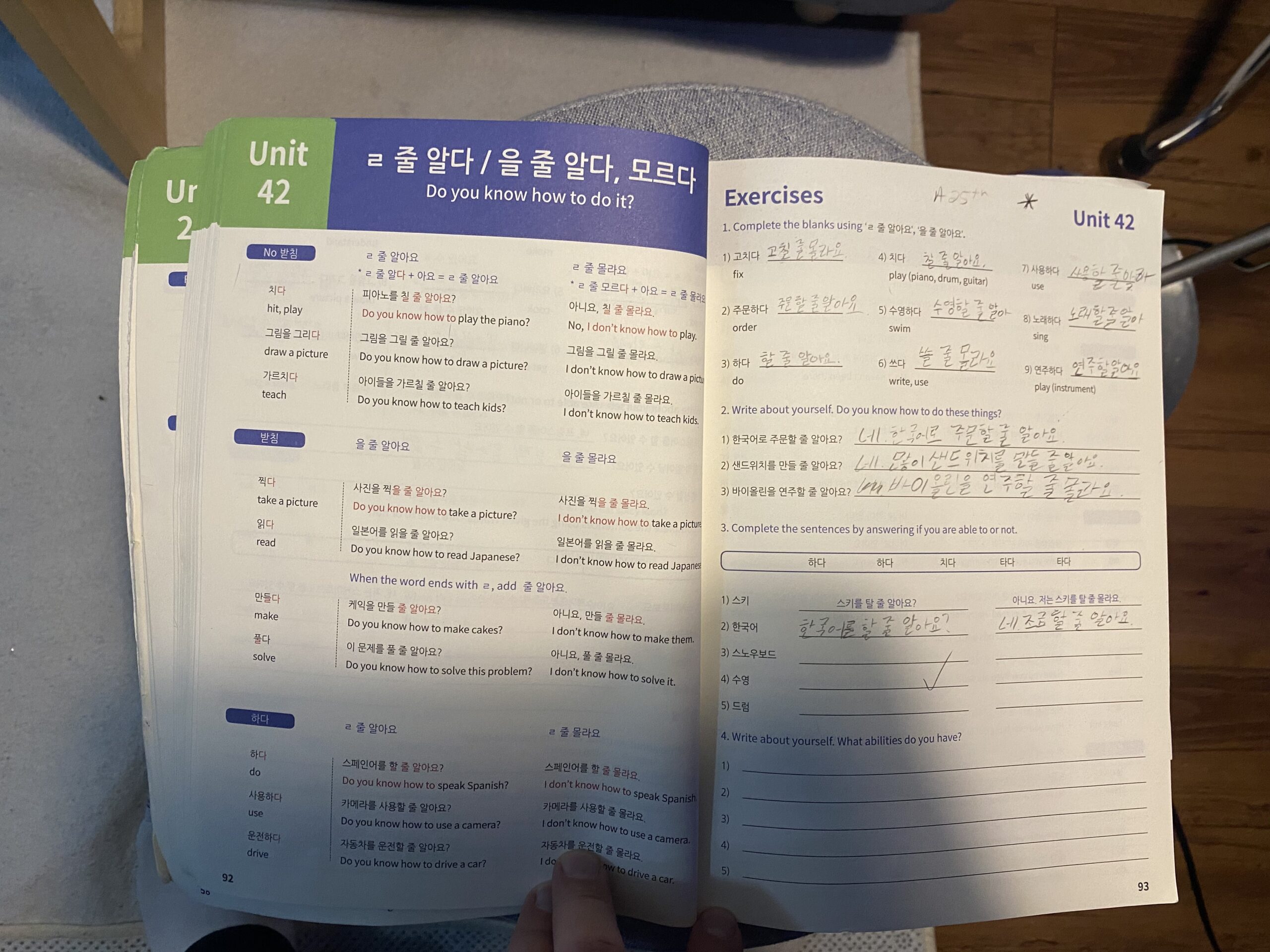

Current level: A2

Highest: B1 (summer 2021)

Goal: I want to take the TOPIK exam and score a Level 3-4 (B1-B2), Korea’s official language test. However, learning Korean more in-depth is a formidable and time-consuming task. Time that I don’t have currently.

Current level: A2

Highest: A2

Goal: I should know more about this because I became a dual U.S.-Italian citizen in 2024. Spanish helps. But given that I’m a citizen now, I must study.

Level: Native

Goal: To consistently expand my vocabulary and creative ways of expressing myself to improve my copywriting business.

Learning a new language makes traveling to a new country and communicating with its people possible, sure. But the real benefit, in my opinion, is that it opens you up to a new way of thinking. It challenges your mind to process ideas differently than your native language would allow.

I have zero hard data on this, but from personal experience, I feel like it keeps my cognitive abilities sharp – even when it comes to using English, my native language, more effectively. Because it makes me appreciate the why behind certain structures and idioms in English.

Here’s an example of what I mean using Italian (my 4th language):

I coined the phrase, “What’s formal (in English) is normal (in Italian),” or “What’s normal (in Italian) is formal (in English).” Either way, it’s the same idea.

Do the servers deserve a tip? Yes / No.

In my experience learning Italian, I’ve noticed it’s changed the way I think and even helped expand my English vocabulary. When I encounter an Italian word resembling its English counterpart, I can often make sense of it through context.

Oreo in Korean / Konglish happens to really resemble the actual English letters of the word “Oreo”

I would be remiss if I didn’t talk about this. I lived in Korea from 2019 to 2022 and just returned from a visit in December 2024.

Apart from Koreans using English in advertisements in absolutely hilarious ways (image above taken Dec. 2024), the concept of Konglish is truly mind-blowing.

Konglish is the (very convenient for English speakers) hybrid of Korean and English, where English words are adapted into Korean phonetics with new meanings, pronunciations, or contexts.

Some are direct borrowings with Korean phonetics applied, while others evolve into entirely unique phrases that can baffle even native English speakers—some require a few leaps in logic to understand.

In fact, Konglish is now so ingrained in the language that even native Korean speakers are sometimes unaware they’re using English words, albeit with Korean adaptations.

And the list goes on and on.

If you have any questions about what it means to really learn a language, ditch the polyfluencers and drop me a message instead.